About these slides¶

- Goal is the least that you need to know

- All slides are created in Jupyter notebooks - free to use and open source

- Github repo

- pyglide provides the interactivity

Part 2 Measurement¶

Measurement¶

- Key principle: repeatability - if you measure a subject twice do you get the same value

- Key principle in measuring repeatability: compare intra-subject variation to inter-subject variation

- Repeatability is relatively easy to measure, since we can take technical replicates

- Repeatability does not measure validity, the extent to which a measure actually measures what it's reported to

In [4]:

## Code used to generate figures

import part2_code

Low inter-subject variability to intra-subject variability¶

In [ ]:

part2_code.measurement1()

High inter-subject variability to intra-subject variability¶

In [ ]:

part2_code.measurement2()

ICC¶

- The intra-class correlation coefficient is a measure of repeatability

- ICC is the proportion of the total variability that is inter-subject

- Note the inter-subject varability is dependent on the sample characteristics

- Suppose older subjects tend to have higher mean values

- A sample of older and younger subjects will have more inter-subject variability than one of just older subjects or just younger subjects alone

Estimation¶

- Usually estimation follows by random effect models; we'll show the basics

- $i$ = subject; $j$ = measurement within subject (assume $j=1,2$)

- $U_i$ is the effect of subject $i$; variation in $U_i$ is inter-subject variation, $\sigma^2_u$

- $\epsilon_{ij}$ is the error; variation in $\epsilon_{ij}$ is intra-subject variation, $\sigma^2$

Estimation continued¶

- Notice that: $$Y_{i2} - Y_{i1} = \epsilon_{i2} - \epsilon_{i1}$$

- Implying $$Var(Y_{i2} - Y_{i1}) = 2\sigma^2$$

- And also that: $$\frac{1}{2}(Y_{i2} + Y_{i1}) = U_i + \frac{1}{2}(\epsilon_{i2} + \epsilon_{i1})$$

- Implying $$Var\left[\frac{1}{2}(Y_{i2} + Y_{i1})\right] = \sigma_u^2 + \frac{\sigma^2}{2}$$

Estimation continued¶

- So we can get: $$\frac{1}{2} Var(Y_{i2} - Y_{i1}) = \sigma^2$$

- And : $$Var\left[(\frac{1}{2}(Y_{i2} + Y_{i1})\right] - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} = \sigma^2_u$$

Example measuring CSF¶

- Below we show repeated measurements of human brain ventricle size on 20 subjects

- We first show a scatterplot then a so-called Tukey mean/difference plot, also called a Bland/Altman plot

Reading in the data¶

In [ ]:

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

visit1 = pd.read_csv("assets/visit1_mricloud.csv")

visit2 = pd.read_csv("assets/visit2_mricloud.csv")

csf1 = visit1[(visit1['Type'] == 1) & (visit1['Level'] == 1)

& (visit1['Object'] == 'CSF')]['Volume']

csf2 = visit2[(visit2['Type'] == 1) & (visit2['Level'] == 1)

& (visit2['Object'] == 'CSF')]['Volume']

plt.scatter(csf1, csf2);

In [ ]:

import statsmodels.api as sm

sm.graphics.mean_diff_plot(csf1, csf2)

plt.show()

In [ ]:

import numpy as np

sm.graphics.mean_diff_plot(np.log(csf1), np.log(csf2))

plt.show()

In [ ]:

## Calculating the ICC manually

sigmasq = np.var(np.log(csf1) - np.log(csf2))

sigmausq = np.var(0.5 * np.log(csf1) + 0.5 * np.log(csf2)) - sigmasq/2

print(100 * sigmausq / (sigmausq + sigmasq))

98.84502763511378

Notes¶

- This is not how one typically estimates ICC anymore; mixed models are typically used

- The subtraction can result in a negative variance estimate

In [ ]:

#### Fitting the random effect model

import pingouin as pg

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

csfdf1 = visit1[(visit1['Type'] == 1) & (visit1['Level'] == 1)

& (visit1['Object'] == 'CSF')]

csfdf2 = visit2[(visit2['Type'] == 1) & (visit2['Level'] == 1)

& (visit2['Object'] == 'CSF')]

csfdf = pd.concat( [csfdf1, csfdf2] )

csfdf['logvolume'] = np.log(csfdf['Volume'])

md = smf.mixedlm("logvolume ~ 1", csfdf, groups=csfdf["ID"]).fit()

md.summary()

Out[ ]:

| Model: | MixedLM | Dependent Variable: | logvolume |

| No. Observations: | 38 | Method: | REML |

| No. Groups: | 19 | Scale: | 0.0003 |

| Min. group size: | 2 | Log-Likelihood: | 41.9000 |

| Max. group size: | 2 | Converged: | Yes |

| Mean group size: | 2.0 |

| Coef. | Std.Err. | z | P>|z| | [0.025 | 0.975] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 11.345 | 0.055 | 207.545 | 0.000 | 11.237 | 11.452 |

| Group Var | 0.057 | 1.491 |

Example¶

Calculation of ICC in the same example using the mixedlm function.

Final answer will be copied here

Example of repeatability studies¶

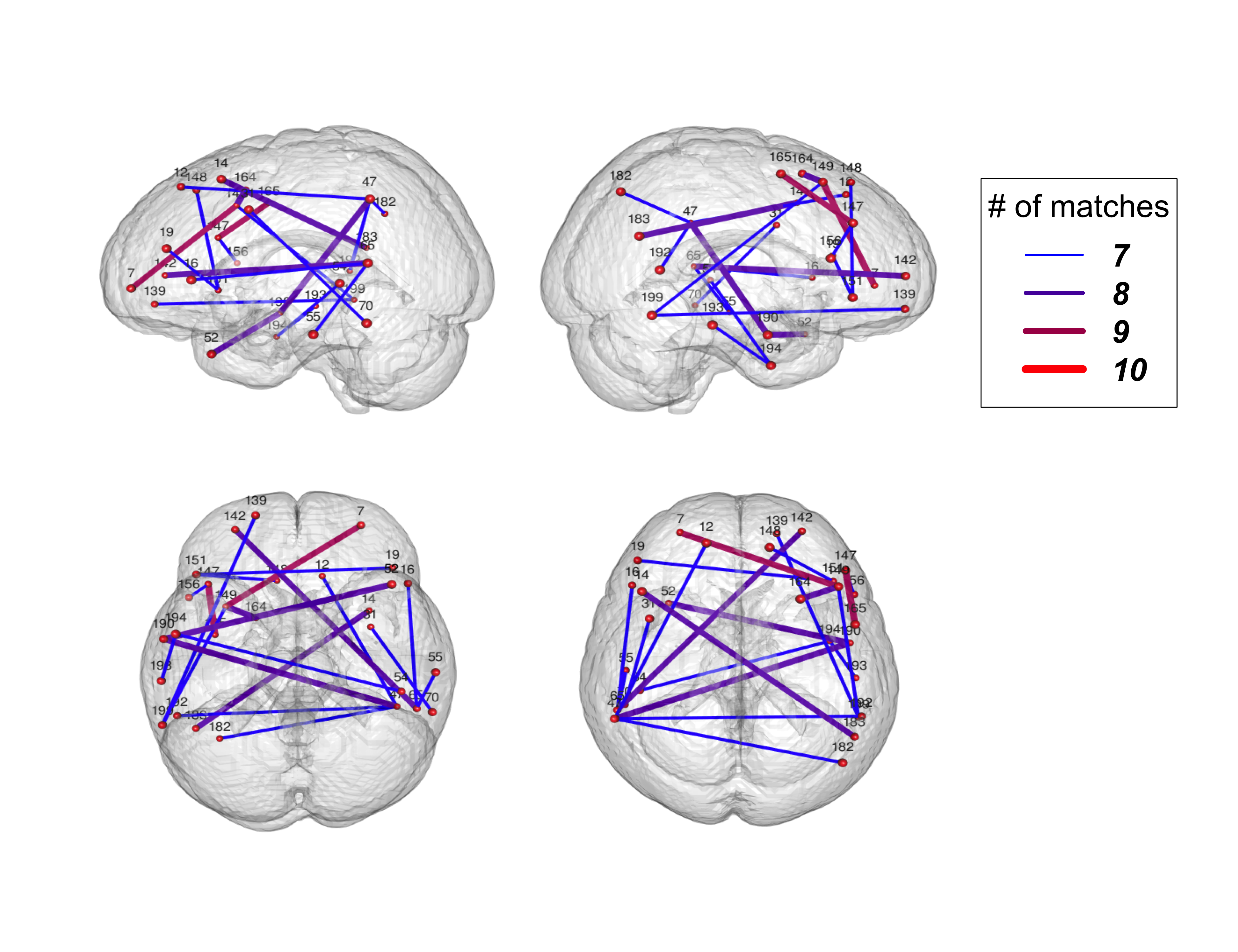

- In functional brain imaging one typically looks at the correlation in activity over time between brain regions

- These sets of correlations estimate how different areas of the brain coordinate

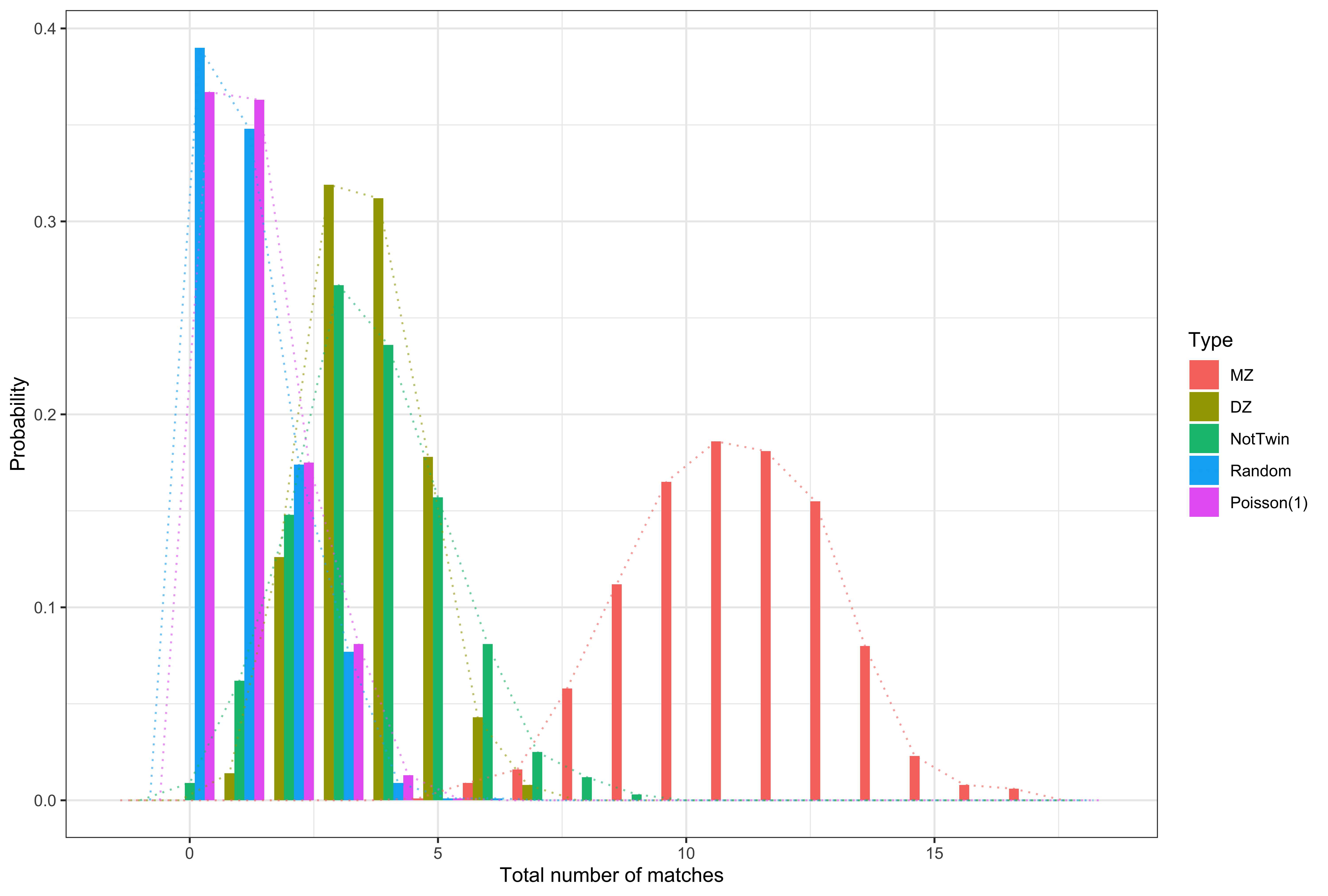

- Finn et al. (Nature Neuroscience 2015) used brain connectivity as a "fingerprint"

- They took pairs of measurements for subjects and found which measurements were the closest

- The count of the number of instances where a subject matched to themselves is a repeatability metric. They called it the "functional connectome fingerprint"

Fun fact¶

- In 1713 Montmort published his letters with Nicholaus Bernoulli

- In them he demonstrated that under independence, i.e. that fingerprints are being matched only by chance, the number of matches follows what is now called Montmort's matching distribution

- This distribution limits to a Poisson(1)

- Wang (2021, Canadian Journal of Statistics) showed that any reasonable matching strategy also limits to a Poisson(1)

- The convergence is quite fast

Courtesy of Wang et al. (2021 Canadian Journal of Statistics)

Courtesy of Wang et al. (2021 Canadian Journal of Statistics)

Validity¶

- Repeatability is not a measure of validity, that a construct measures what it purports to

- Repeatability is easy to measure, since we can collect technical replicates, observe units over short periods of time and so on

- Validity is often hard because the measurement we'd like to validate is the current best measure of the thing we'd like to estimate!

Things to try¶

- In the absence of a measurment gold standard, the statistical proceduer I find most useful is Predictive validity: is the measurement associated with outcomes that it should be?

- Also useful, concurrent validity is the measurement correlated with other measures of the target?

- Example: in a poor country where child ages are hard to determine due to poor record keeping an image based DL algorithm is used to estimate age.

- Repeatability - take different pictures of the same subject, do the predicted ages agree?

- Predictive validity - does the estimated age predict developmental milestones at roughly the right time

- Concurrent validity - is the estimated age correlated with height, weight and other measures of size